Ghana, NCECA Residency 2010. An Extreme Case of Creation

from the left, Abisboba, Sharon (nicknamed Ayampok-beire- ‘little Ayampoka’), Ayampoka and Faustina pounding clay at SWOPA.

from the left, Abisboba, Sharon (nicknamed Ayampok-beire- ‘little Ayampoka’), Ayampoka and Faustina pounding clay at SWOPA.

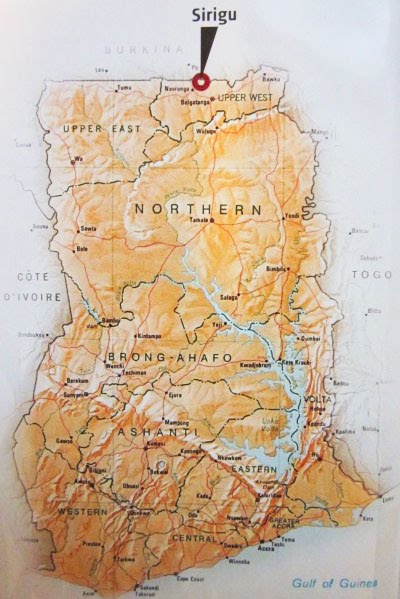

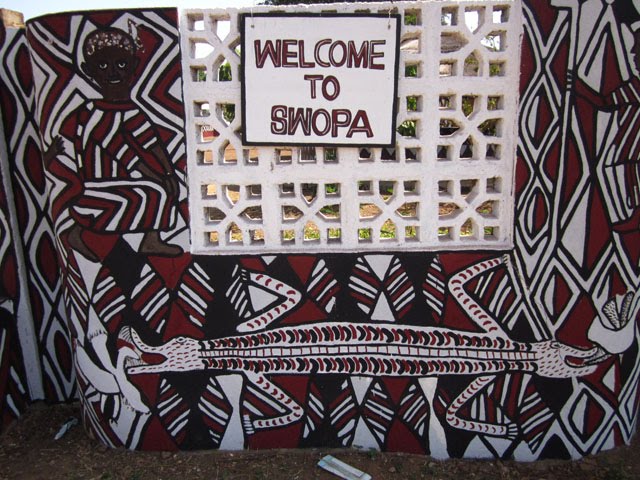

Sharon Virtue in Ghana with SWOPA(Sirigu Womens Organization for Pottery and Art.)

Typical house of the region. This section of the compound is called the Denyanga. this contains the rooms for the eldest woman living in the compound.

Ayampoka and me, ‘Ayampok-beire’ (as they nicknamed me little Ayampoka). Waiting for the fire to cool down outside her house.

Ayampoka and me, ‘Ayampok-beire’ (as they nicknamed me little Ayampoka). Waiting for the fire to cool down outside her house. The beautiful local kiddies that would watch and help out when i needed it. They were like little birds.

The beautiful local kiddies that would watch and help out when i needed it. They were like little birds.

For more images of the work created on this residency go to:

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.343710682346488.93912.178807228836835&type=1

This residency provided me a sense of freedom. I felt excited, playful and unattached to the outcome. It helped me to achieve a method of exploration that I had not had the courage to try in the studio setting. I know this will be a benefit to my growth as an artist in the future. I’m honored to have been a part of it, even for a short time. I have learned so much, not just about the Nankani tribe and culture, but also about myself, my work and my process of creation.